The icons we make

Mother Agnes Mariam is an iconographer. She learned the ancient techniques of Byzantine painting in the Carmelite monastery of Harissa in Lebanon where she lived for 21 years. In this article we present how she got to know the Church of Antioch - the mother church of Arabic icons. In the second part of the article we will explain the origin of the Arabic icon, its style and meaning.

The discovery of Mother Agnes of the Church of Antioch

Mother Agnes Mariam: "In 1983, a Lebanese monk visited our monastery [1]. He was carrying a large icon of the Virgin Mary (Our Lady of Ilige - shown here on the left), which had suffered a lot during the war. He asked us to restore it. While working on the icon, I noticed that it had five underlying layers. These layers (the oldest dating from the 10th century) were like a summary of the whole history of the Maronite Christians in the Middle East. When I started to study the layers I made a discovery that shocked me and determined the rest of my life: the discovery of the Church of Antioch, my own Church, whose importance I ignored! [2] It was like someone talking to a Catholic about the Church of Rome and he would say, "What, where is it?” I was overwhelmed, how was it possible that I had left everything for Christ when I entered the Carmel and I didn't know my own Church?

I realized that the Christians in this region - Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Iraq and Jordan - are called to a great mission, but most have forgotten it. The persecution and hostile attitude towards Christians have left them tired. Today they see life in the land of their ancestors more as a survival – that is a material survival.

It all starts with cultural identity for a Christian. At Pentecost the Holy Spirit confirmed this identity. The Apostles, upon whom the tongues of fire had descended, began to proclaim the miracles of God. Everyone present heard the message of salvation in their own language! This demonstrates the importance the Holy Spirit places on the identity of every person and every people.

Arab icons

Thus, through iconography, Mother Agnes-Mariam discovered her own Church. It was in this context that she became increasingly interested in local iconography: Melkite icons, also called Arab-Christian or simply Arab icons. She organized several exhibitions of Arab icons in Europe. In October 2002, the exhibition The Splendour of the Christian East opened at the Icon Museum in Frankfurt and was a great success. In May 2003, the same icons and liturgical objects, together with some thirty Arabic, Syriac and Karshouni (Arabic written in Syriac letters) manuscripts, were produced in the prestigious halls of the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, under the title Icônes Arabes, Art Chrétien du Levant. In October 2004, a reduced number of these same icons, but completed by other productions of the same style and Coptic works, were the subject of a new exhibition, under the title From the hands of your servant, at the Frankfurt Museum on the occasion of the International Book Fair, dedicated to the Arab civilization.

Given the interest in Arabic icons in the West Mother Agnes-Mariam has written an illustrated book with examples of the most prestigious Melkite icons, under the title: Arabic Icons - Mysteries of the East. In the following we share with you a few glimpses from the introduction.

Itinerary of early Christian art

It is in the East, where light dawns, that the icon is born. Its path is that of the Judeo-Christian Revelation which affirms that God is Light and that He has been seen among men. Judeo-Christianity has never been reluctant to borrow from neighboring civilizations, enriching them with its vision of the sacred.

The first Christian representations dating from the time of the persecutions (2nd-3rd centuries), touch us by the celestial unction in which they are bathed: the figures of the Good Shepherd or the Mother of God. It was not until the Edict of Milan (313), with the freedom of worship granted by the Emperor Constantine, that the Church and, with it, figurative sacred art, came into the open. Thanks to the magnificence of the Emperor and his mother, Saint Helena, basilicas were built in Rome, Palestine and throughout Christendom. Sparkling mosaics adorned the interior of the sacred monuments. Etheria wrote in her Travel Diary: "And what can be said of the decoration of the buildings by Constantine, under the supervision of his mother, employing all the resources of his empire, adorned with gold, mosaics, and precious marbles" [3]

This "royal" art proved to be of astonishing maturity. It was at this time that most of the main feasts of the liturgical calendar were fixed with the iconographic compositions that corresponded to them. The magnificent mosaics were not only contemplated in the basilicas and churches, but were also venerated in the domestic space. Thus, the portable icon came to fulfill man's desire to carry and keep in his home the representation of the divine, like the domestic altars erected in honor of the Emperor in the last years of Rome. The different schools of iconography developed according to the spread of the Gospel in the different cultures but also according to historical vicissitudes.

Traditional foundations of iconography

Monotheistic sacred art found in Christianity the humus that would make it bear fruit with the necessary justifications for its existence. If all figuration was forbidden in the Old Testament, the reality of the divine Incarnation made iconographic expression not only legitimate but necessary, because it was willed by God.

When the iconographer wants to paint an icon, it is customary for him to recite a prayer [4] in which he mentions two primordial events reported by tradition and which are like the founding elements of Christian iconography: the story of the first icon of Christ "not made with human hands" - the mandylion - and the icon of the Mother of God, painted by the apostle Saint Luke.

The tradition of the Mandylion

As early as the fourth century, a tradition is attested [5] according to which Abgar Ukhomo [6], king of Edessa [7], sent a delegation to Christ asking him to come to his kingdom. Christ is

said to have written personally to Abgar. To this original source, another source was added a little later, of which St. John Damascene, among many others, mentions that Abgar, a leper, asked

Christ to come to Edessa to heal him. The Lord, unable to leave the Holy Land, took a cloth (mandylion) and applied it to his face, which became imprinted. The image of Christ, carried by the

emissaries, or by the apostle Thadeus, healed the king as soon as he applied it to his flesh. A beautiful icon from Mt. Sinai depicts the scene: King Abgar, seated on his throne, disfigured

by leprosy, carries the mandylion on which is printed the face of Christ.

The tradition of the Mandylion is the foundation of Christian iconography, making it an institution of divine right. The first image of Christ would be divine and, for this reason, called

"not made with human hands". If God, in the Old Testament, invited Moses to contemplate the model manifested in heaven in order to make a copy of it (Ex 25:40), here the iconographic model

par excellence, the Mandylion of the face of Christ, is given on earth so that men may reproduce it without fear.

The transition to frontality

The tradition of the Mandylion originated in Syro-Mesopotamian circles. The face of Christ,

as seen on the Mandylion, bears a striking resemblance to the frontal figures of the Sassanid kings (224-651), represented without necks and with pointed beards. Sassanid art, which emerged

from a great intermingling of civilizations in Mesopotamia, opted for the frontality that was adopted by Christian art. Egyptian and Assyrian-Babylonian representations were in profile. The

Sassanids took this decisive step.

This transition to frontality is crucial. Frontality introduces the notion of the divine presence in front of the human. Art ceases to be episodic, it becomes epiphanic. The icon will bring

to the highest degree this personalization of the divine. It no longer represents the history or the mythical epic of the king-hero or the god, but reveals a mystery, a theophany. The

frontality adopted by Christian iconography seeks to manifest the divine presence that has become visible to the eyes of men.

The tradition of the icon painted by the holy apostle Luke

The second founding tradition of Christian iconography says that the first iconographer was

the evangelist St. Luke, a native of Antioch. He is said to have painted the Mother of God during his lifetime. In the 14th century, Nicephorus Callistus attests to a tradition according to

which, according to the testimony of Theodore the Reader

(6th-7th centuries), the empress Eudoxia sent Pulcheria a portrait of the Mother of God painted by Saint Luke. The latter would have deposited it in the church known as "of the

Guides" (or Hodigoon, hence the name Hodigitria). The icon of the Mother of God painted by the holy apostle Luke is also designated as "not made by human hands". It founds the apostolic

origin of the icon. If the Mandylion is the icon par excellence, that of the Mother of God condenses the Economy of Salvation. Indeed, the Virgin who holds in her arms the Child God is the

eloquent proclamation of the mystery of the Incarnation.

The icon will be inserted into the internal dynamics of the liturgy which raises our earthly reality towards heaven and makes us enter into the eternal today of God. However, the theological

foundations of sacred art will only be definitively established by the successive purifications due to iconoclasm.

Iconoclasm (breakers of icons)

for a clearer vision

The tendency to repudiate the figurative has always existed in the East, and it appears to be an overcoming of the impossible quest to express the ineffable Invisible. Iconoclasm can be traced back to the pharaoh Akhenaten (1372-1354 BC). This pharaoh, considered the father of monotheism, declared the Sun, Aten, the one and only deity, and ordered the temples of other deities to be closed and their statues destroyed.

The Israelites have always refused to represent the divine: "You shall not

make for yourself any graven image, any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth" (Dt 5:8). But from the

beginning there is an exception: the Tent of the Testimony has two cherubim with human faces, carved in pure gold. These two cherubim spread their wings over the mercy seat (Ex 25:18).

The space between their wings is precisely the place where the God of Israel is manifested (Num 7:89). In the Temple of Solomon, we find the figure of the cherubim with human faces on the

perimeter of the walls and the doors in addition to the mercy seat (1 Kings 6:29-32).

How is it that, in spite of the aniconic prohibition, there is a figuration in the cult of the first Covenant? It is a matter of divine pedagogy both in relation to the image and to the

vision. Concerning the image: the icon is linked to the most fundamental identity of man, who, according to biblical revelation, is created in the Image of God. The ambiguity of the image is

linked to the fall (Gn 3:1-22) which breaks the existential relationship between man as image of God and God, the archetype of man, preventing man from transcending his being image to

go back to his archetype. Now, to stop at the image and forget the archetype is idolatrous. Hence the danger of the image.

Concerning vision: the cherubim are precisely the angels of vision: "Their whole body, their backs, their hands and their wings were full of eyes" (Ezk 10:12). To see the Ineffable,

one must be entirely receptive to vision: to have the eyes of the heart opened by Faith. Without these eyes, which the Fathers call "the eye of the dove", the gaze cast on the image cannot

become the vision of God. The door of Paradise is guarded by the Cherub with the flaming sword (Gen 3:24): he is charged to remind man of his origin, he does not allow man to return to

Paradise until the Image of God has been reconstituted in him, without which his relationship to the divine would be idolatrous.

The first iconoclastic crisis of Christianity dates back to the second century A.D. and concerns the mystery of the Cross. The docetists and aphtar-docetists refused to show Christ on the

Cross. It was said that a splendour had come to hide him and that no one had seen him crucified. Therefore, until the 4th century there were very few representations of Christ on

the cross. This heresy has passed into Islam, which cannot tolerate crucifixion.

The most significant iconoclastic crisis lasted for almost one hundred and twenty years (726-842). The iconoclasts (breakers of icons) and the iconodules (lovers of icons) fought a merciless war.

The icon emerged triumphant from this struggle with a solid theological explanation thanks to great doctors such as St. John Damascene, Theodore Abuqurra - both of Arab-Christian culture -

Theodore Studite and Maximus the Confessor, of Greek culture. These Eastern theologians of the icon clearly affirm: God, whom nobody saw and whom it was forbidden to represent in the Old

Testament, in order not to fall into idolatrous schemes, became visible. Since God has been seen by the eyes of flesh, it is now possible to represent Him. The icon becomes the sure means of

expressing the greatest manifestation of God in history: the Incarnation, which gave a Face to the Word of God in dialogue with man since the beginning of time. The icon recalls what the

Church keeps in precious deposit as a memory of the Faith. Revelation reaches men through a transmission, an uninterrupted traditio from Christ to the Apostles and from them to their

successors until our days. There is a transmission of Faith as dogma and there is a transmission of Faith as vision. Thus, the ministry of the iconographer is apostolic and sacred iconography

is a transmission of the vision of Faith: revelation of the Face. It will not be difficult to note the great resemblance of the faces of the adult Christ from the origins to the present

day.

As long as history lasts, man will want to look at the icon to contemplate the Glory of the living God to which he secretly aspires: he will see the vision of those who had the privilege of

being contemporaries of Christ and who announced to humanity what their eyes have seen, what their ears have heard and what their hands have touched of the Word of life (1 Jn

1:1).

Christian Iconography in Islamic Lands

The iconoclastic crisis is concomitant, to within a few decades, with the Arab-Muslim conquest. The state of research does not allow us to say whether Islam influenced this crisis or whether it emanated from heterodox currents proper to a late Judeo-Christianity that would itself have influenced Islam in the direction of iconophobia.

Most of the rare icons or pictorial representations that escaped the iconoclastic

massacre are to be found in the monastery of Saint Catherine of Sinai and were spared because they were in Islamic lands, outside the jurisdiction of the Byzantine basileus. Moreover,

the first Muslim ruling dynasties were in favor of anthropomorphic representations outside the places of worship. We can still contemplate the beautiful frescoes of the Umayyad palaces in the

desert. Is it not reported of Mohamed that when he was about to destroy all the polytheistic signs in Mecca, he prevented his followers from erasing the icon of Christ and that of the Virgin,

each painted on a pillar of the sanctuary? [10]

Thus the Christians of that region have always painted and venerated icons. In the apologetic treatise Dispute against the Arabs, by Abraham of Beit Halé, dating from the

eighth century, the Syriac monk speaks of icons in this way: "We prostrate ourselves and honour his image because He has imprinted it with his Face and given it to us. Every time we

look at His image we see Him. We honor the image of the King because of the King.

There are many witnesses to the iconographic activity of Christians under Muslim rule. There was, of course, an artistic abundance due to the period of calm resulting from the temporary victory of the Crusaders, but iconographic activity continued after the withdrawal of the Western armies. Clearly, despite the severe measures taken against Christians by the Fatimids, then the Ayyubids and above all the Mamluks, who considered them to be subservient to the West, the Christians continued to practice their art and to represent their mysteries.

Many iconographic works have had to face the ravages of man and time. Many of

them have perished or have been badly damaged. It was on the basis of these premises that Arab-Christian art developed, waiting for the political circumstances to become more

favourable.

Arab-Christian art, the flagship of the Arab

Renaissance

Why do we identify certain icons as Arab and the art from which they emanate as Melkite or "Arab-Christian"? The term melkite comes from the Syriac melkoye. It was a nickname for the "agents" of the Byzantine king-occupier, the melkoyo. This is the name given to the faithful of the Council of Chalcedon (481), especially those of the Patriarchate of Antioch who joined Rome in the 18thèmecentury.

The term Arab is contemporary. It encompasses various identities that reoccupy each other, complement each other but can also clash. If it has a religious connotation in that Islam is the religion of the Arabs by antonomasia, the term Arab is not identified with Muslim. The contemporary consciousness of an "Arab" belonging emanates from an awakening and a socio-cultural and political struggle that took the name of the Arab Renaissance in history - Arab designating not the ethnic group but the culture that was the torchbearer of these upheavals against the Ottoman hegemony. Later, Arabism would rise up against Western imperialism.

The art of the Arabic-speaking Christians developed at the time when the Ottoman Empire opened its doors to the West. The Ottoman military decline began in 1683. Weakened by the setbacks inflicted by the Christian coalition of the Holy Alliance, the Sublime Porte opened its doors to the Europeans, who assigned consuls and commercial agents to the major cities, followed by the Latin religious orders. Aleppo, the third city of the Ottoman Empire, was the privileged place of this meeting between East and West. In 1548, the Venetian consulate opened there, which allowed the arrival of the Franciscans in 1571. In 1562, the French consulate was inaugurated, accompanied by the Capuchins. The Carmelites were present from 1623, the Jesuits from 1625. The Lazarists settled in Aleppo in 1773.

The missionaries founded convents and schools. They spread Western spirituality by translating spiritual authors into Arabic and successfully preached the rallying to Catholicism and the

Papacy. Some of the Melkites of the Patriarchate of Antioch united with Rome in 1724, followed by Jacobites and Armenians. A vast cultural and religious current emerged, taking advantage of

the new political situation and the commercial boom in Aleppo, thanks to its privileged location on the silk and spice route. What would later be called the Arab Renaissance was

carried out by personalities belonging to the various Christian and Muslim communities.

The foundation of the Maronite College in Rome in 1584 had encouraged the training of Catholic elites from Lebanon, Syria and Cyprus. The taking over of the thousand-year-old monastery of Saint Sabbas by the Christians of Istanbul galvanized the Orthodox youth of Aleppo, who came to draw on the sources of Eastern spirituality. The Arab Renaissance finally crystallized around the Maronite bishop of Aleppo, Germanos Farhat (1670-1732). Five oriental religious orders were founded in Aleppo in the wake of this Renaissance.

Arab icons, particularities of a new world

Sacred art took part in the cultural movement of the Nahdah, or Arab Renaissance. Iconographers and copyists were stimulated by local scholars and patrons. They worked for the Orthodox as well as for the Catholics. By appearing in Aleppo in the XVIth century the Arab icon seems to be an emanation of post-Byzantine art but a thorough study of the style and technique shows that it carries an enormous mixture of cultures.

While remaining faithful to traditional Byzantine or Syriac themes and technique, Arab-Christian art willingly opened itself up to Latinizing subjects that it worked on in the oriental manner, revealing the dogmatic inclination towards Catholicism of some of the commissioners, if not the painters themselves. He also let himself be influenced by Islamic culture and the surrounding oriental environment. This creates an interesting and unique symbiosis.

The subjects treated are spiritual, even fashionable, but they are characterized by a great doctrinal certainty and a not inconsiderable theological depth. Stylistically, Melkite art oscillates between a conformism faithful to the traditional canons and a fiery creativity in the wake of post-Byzantine art. For some icons, it is difficult to discern whether the hand is Greek or Melkite, so similar is the style.

Let us be seduced by a new and diversified aesthetic language which will reveal

to us the soul of the Christians of the East, at a privileged moment of their history, so often tormented.

The following are two examples of Arabic

ions.

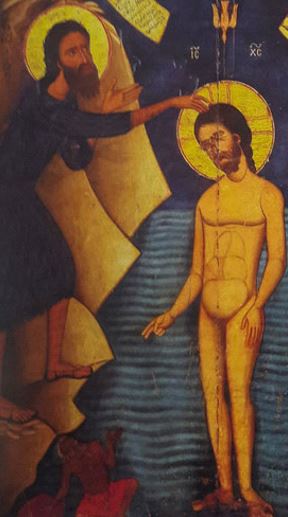

1. The Baptism of Christ

The Baptismal icon is a complete baptismal catechesis. By its style, it is similar to the first representations of the genre where Christ is still completely naked, like the New Adam in Paradise.

St. John the Baptist looks at the dove descending from the celestial semi-circle. With his left hand, he draws the gesture of intercession, and places his other hand on the head of Christ, making the gesture of baptizing him. Christ stands with his head bowed, in the attitude of the Suffering Servant who stoops to lift up the many. The bowed head signifies the death of Christ who, according to the Gospel of St John, "bowed his head and gave up the ghost" (Jn 19:30). Jesus is standing in the dark waters of the Jordan River which represent our death. The whole theme of Christian baptism lies in these two movements signifying the death and resurrection of Christ: buried in his death, we rise with him. Similarly, baptism by immersion, proper to the Eastern tradition, signifies this descent into the death of Christ. The rising of the water signifies the resurrection.

Bottom left:

An old man is crouching and looking back, carrying an amphora. This is the personification of the

Jordan River, a river god, as in the Greco-Roman tradition. His

presence illustrates the verses of the psalm.

In the upper left corner, the holy King David carries a scroll written in Arabic:

"the sea saw it and fled, the Jordan turned back. the hills like lambs. What is the matter with you, O sea, that you flee and you, Jordan, that you turn back? The waters saw you, O God, the waters saw you and they were moved. "

(Excerpts from Psalms 114 and 87 proper to the Byzantine liturgy of the Feast of Baptism).

To the left of Christ, the six angels are the "protoctist" angels, proper to the Judeo-Christian tradition. In their commentaries on Genesis, the ancient authors (rabbis, gnostics, Christians) affirm that for each day of the Creation, an angel came out of God's hands to watch over his work. In Judeo-Christian thought, the six angels associated with the first creation were also naturally to be associated with the second, much more important one, which was Baptism. It was this idea that influenced the iconography of baptism, in which Christ was represented in the Jordan surrounded by angels. They stand in the attitude of servants and witnesses of the mystery. This is signified by the cloth they carry to dry Christ coming out of the water, but also as a sign of reverence before the mystery of the lowering of the Son of God. Indeed, the hands hidden by the garment signify reverence and submission.

In the upper right corner, the prophet Isaiah holds a phylactery with the following inscriptions in Syriac: "Thus says the Lord, wash yourselves, purify yourselves, remove your wickedness from my sight" (Is 1,6) and "You who are thirsty, come to the waters" (Is 5,1), "you will draw joyfully from the springs of salvation" (Is 12,3) - texts that are proper to the Syriac tradition of the feast of baptism. The title of the icon, The Baptism, is in Greek, it occupies the upper center of the icon. The titles of the characters are also in Greek.

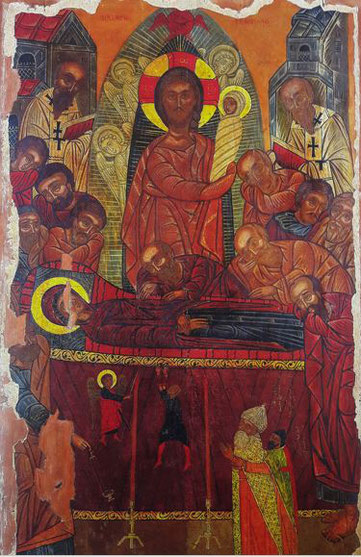

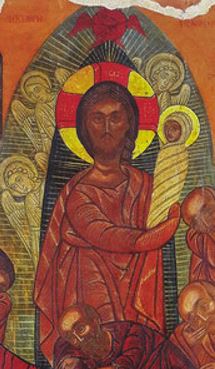

2. Dormition of the Mother of God

The Dormition is inspired by a 5th century apocrypha, the Transitus Mariae of Pseudo-John.

The Mother of God, with both arms crossed at the waist, is lying on a vermilion mattress, with her head resting on a green rectangular cushion, streaked on the sides. She is wearing a navy blue dress and a red maphorion (a cloak that covers the head and shoulders).

Behind the catafalque stands Christ, of imposing stature, in a pale blue-green mandorla.

Jesus appears here to welcome his mother. He receives her soul, represented as a small child wrapped in swaddling clothes and nimbed. On either side, the angelic powers appear, with colours blurred to create the illusion of transparency.

The keystone of the mandorla is closed by a six-winged seraph.

In the foreground, on the left, stands Saint Peter. He raises his left hand, covered as a sign of respectful sorrow, and with the other he is holding the censer for the death ceremony. Opposite him stands St. Paul, his hands covered and his head bowed. Next to him is an apostle who could be James, the Lord's brother, preceded by John the Theologian.

In accordance with the apocryphal tradition, according to which Saint Thomas was not present, there are only eleven Apostles. On his arrival, Thomas was given the benefit of the doubt, which allowed him to open the tomb and see that the Virgin's remains were no longer there, which led to the proclamation of her Assumption into heaven in body and soul.

On either side of the mandorla are two hierarchs: St Hierotheus and St Dionysius Areopagite, mentioned in the apocrypha, wearing white phelonion and omophorion bordered by black crosses. The buildings indicate that this is an intra muros scene.

Further down on the right:

Of smaller dimensions, a bishop wears a Latin tiara, an apitrachilion and a Byzantine phelonion.

Behind him:

Smaller, stands a priest dressed in an alb and a Latin chasuble with a large cross, but with the Syriac kukulos (black cap), which surrounds his arms to hold his hands together.

Notes:

[1] The Carmelite monastery of Harissa in Beirut (Lebanon) where she resided.

[2] Mother Agnes-Mariam was a Carmelite in the Carmel of the Theotokos of Harissa, Beirut. This monastery adopted the Byzantine rite out of love for unity while maintaining its own Latin Carmelite tradition. Thus Mother Agnes-Mariam was largely unaware of the importance of the Patriarchate of Antioch and its history.

[3] Travel Diary, Christian Sources, p. 205

[4] "Lord Jesus Christ, who is infinite in your divinity, who in the fullness of time was willing to be born of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God, thus taking on human nature in a way that surpasses all understanding. You who imprinted the features of your face on the holy shroud and thus brought healing to King Abgar. You who, through your most Holy Spirit, illuminated your holy apostle and Evangelist Luke so that he could reproduce the beauty of your Mother carrying you as a child in her arms. Master of the universe, illuminate, enlighten and strengthen the soul, heart and mind of your servant, and guide his hand so that for your glory and the magnificence of your holy Church he may represent in a worthy and perfect manner your holy image, those of your pure Mother and of all the saints. Grant that he may be safe from the temptations of the devil through the intercession of your all-pure mother, the holy apostle and Evangelist Luke, and all the saints."

[5] Cf. Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History 1,13 and the Doctrine of Addai, Syriac text of the sixth century.

[6] A Syriac term meaning "the black one". In reality, Abgar was a leper.

[7] The present Urfa in Turkey. Small kingdom of eastern Mesopotamia, sometimes vassal of the Romans, sometimes of the Persians.

[8] This is why, in Eastern Christian iconography, the profile becomes the sign of imperfection and even of enmity with God. The devil and Judas are always in profile.

[9] Nowhere does the Qur'an prohibit drawing an image, a shape, but since this term is attached to God's work, the one who engages in such a task is seen as doing God's work and a feared competitor, especially since the image can be the object of worship, and thus promote polytheism. The prohibition of images will proliferate in the Hadith. (cf. Sami A. Aldeeb Abu Sahlieh).

[10] To the Hadith clearly hostile to figurative art, we must point out a fact reported by the historian Al-Azraqi (d. ca. 865). He writes that when Mohammed conquered Mecca, he entered the Ka'ba and found the image of Abraham swearing by the divining arrows, images of angels and those of Mary and Jesus. He took water, brought a cloth, covered the images of Mary and Jesus with his hands, and gave orders to erase everything except what was covered by his hands. Al-Azraqi states that these two images remained in the Kaaba until it was burnt down in 683, that is, more than half a century after the conquest of Mecca. This fact, never denied, but also never mentioned by Muslim authors hostile to figurative art, casts doubt on the authenticity of other accounts to the contrary (ibid.)